Tax Basis: An Excellent Review In 2025

Table of Contents

A Step-By-Step Synopsis On Tax Basis

Tax basis, also referred to as cost basis, is the amount of a taxpayer’s investment in an asset for tax purposes. It serves as the starting point for calculating gain or loss when the asset is sold, exchanged, or otherwise disposed of. The basis determines how much of the value received from the sale of the asset is taxable gain or non-taxable return of capital.

It acts as the “starting value” for tax calculations. A general understanding of basis is essential for:

- Determining capital gains or losses

- Calculating depreciation

- Applying loss limitations in pass-through entities

- Ensuring compliance in gifts, inheritances, and real estate transfers

Tax basis is the starting value used to determine gain or loss for tax purposes. Over time, this basis can change depending on various factors like depreciation, contributions, or inherited value. The IRS recognizes multiple types of basis, depending on how the property was acquired or transferred.

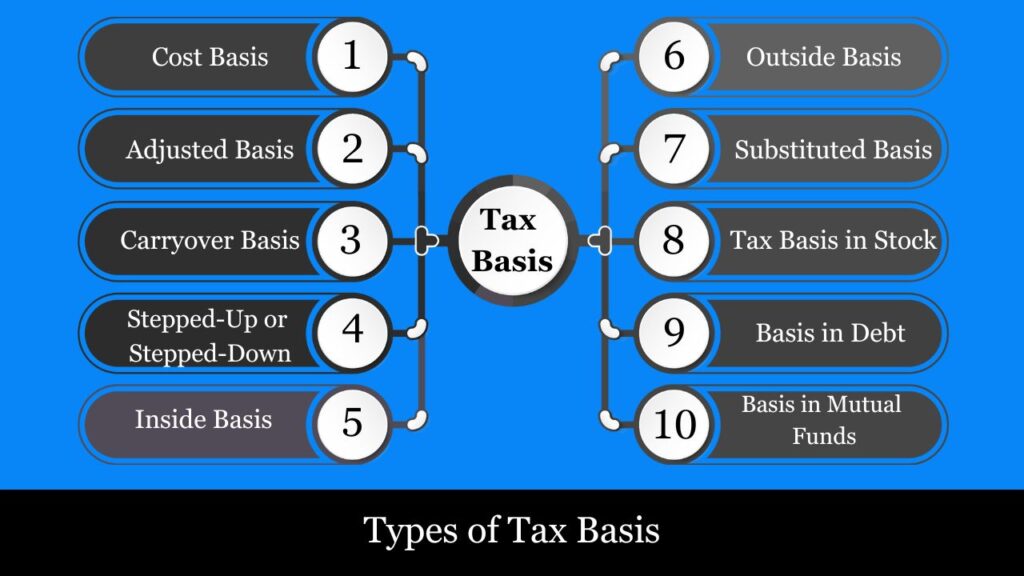

Types of Tax Basis

Over time, this basis can change depending on various factors like depreciation, contributions, or inherited value. The IRS recognizes multiple types of basis, depending on how the property was acquired or transferred.

1. Cost Basis

The most common and foundational type of tax basis is the cost basis, which refers to the original amount paid to acquire an asset, including purchase price and all capitalized costs. This includes expenses such as shipping fees, installation, legal charges, and sales tax. For most personal and business property, this cost basis serves as the starting point for tracking the asset’s adjusted basis over time. Cost basis plays a crucial role in calculating depreciation, amortization, and the gain or loss upon the asset’s sale.

Example

David purchases a parcel of land for $100,000 and incurs an additional $2,000 in related expenses..

His total cost basis in the land is $105,000 ($100,000 + $2,000 + $3,000).

This amount will serve as the initial basis for determining any gain or loss upon the sale of the property.

2. Adjusted Basis

The adjusted basis evolves from the original cost basis by factoring in all increases and decreases made over time. Increases may include capital improvements or reinvested earnings, while decreases typically include depreciation, amortization, casualty losses, or prior deductions taken. The adjusted basis reflects the current tax value of an asset and is critical when calculating gain or loss upon sale, determining the deductibility of losses, and establishing the taxable portion of distributions from entities.

Formula

Adjusted Basis = Original Cost Basis + Increases – Decreases

Example

Maria buys machinery for $30,000. Over three years, she claims $6,000 in depreciation.

Her adjusted basis is reduced to $24,000, after subtracting $6,000 from the original $30,000.

If she sells the machinery for $28,000, her taxable gain is $4,000.

3. Carryover Basis

A carryover basis applies when a taxpayer receives property as a gift. In these situations, the recipient typically inherits the donor’s original cost basis instead of using the property’s fair market value at the time of the gift. This means that any built-in gain or loss carries over to the recipient. However, if the FMV is lower than the donor’s basis, a special dual-basis rule may apply, depending on whether the property is later sold at a gain or a loss.

Example

John gifts his niece Emma 100 shares of stock. He originally bought them for $10,000, and at the time of the gift, the fair market value is $15,000.

Emma’s basis carries over as $10,000, which is identical to John’s initial cost basis.

If she later sells the shares for $18,000, she will report a $8,000 capital gain.

4. Stepped-Up (or Stepped-Down) Basis

A stepped-up basis is granted to beneficiaries who inherit property. In this scenario, the basis of the inherited asset is adjusted to reflect its fair market value as of the decedent’s date of death. This eliminates any capital gain that accrued during the decedent’s lifetime, allowing heirs to sell the asset with little to no tax liability. This treatment is widely considered a major tax planning advantage in estate transfers.

Example

Sylvia inherits a house from her father, who bought it for $150,000. On the date of his death, the house’s fair market value is $400,000.

Sylvia’s new basis in the home is $400,000, reflecting the stepped-up value rather than the original $150,000.

If she sells it shortly after for $405,000, her taxable gain is only $5,000.

5. Inside Basis

The inside basis represents the tax basis that a partnership or other business entity has in its individual assets. It reflects the entity’s investment in its property, including purchases, capital improvements, and adjustments for depreciation. Inside basis is important for determining entity-level gain or loss upon sale of those assets and is separate from the basis held by individual partners or shareholders in their ownership interest.

Example – Inside Basis

ABC Partnership buys equipment for $50,000. This $50,000 becomes the inside basis of the asset for the partnership—it represents what the partnership invested in the equipment.

Later, the equipment is depreciated by $10,000. The inside basis has been adjusted to $40,000, accounting for the $50,000 original cost minus $10,000 in accumulated depreciation.

This inside basis will determine gain or loss if the partnership sells the equipment in the future.

6. Outside Basis

The outside basis refers to the tax basis an individual partner or shareholder has in their interest in a pass-through entity like a partnership or S corporation. This includes the amount they invested, increased by income and additional contributions, and reduced by losses, deductions, and distributions. Outside basis determines how much loss an owner can deduct, whether a distribution is taxable, and the gain or loss upon sale of the interest.

Example

Lena invests $50,000 in a partnership. During the year, her share of partnership income is $10,000, and she receives a $5,000 distribution.

Her outside basis is calculated as:

$50,000 (initial investment)

- $10,000 (income share)

– $5,000 (distribution)

= $55,000 (new outside basis)

This basis determines how much loss Lena can deduct or gain she must report if she sells her partnership interest.

7. Substituted Basis

A substituted basis arises when one asset is exchanged for another, such as in a like-kind exchange under IRC §1031. Instead of recognizing gain or loss at the time of exchange, the taxpayer’s basis in the new asset becomes the same as the basis in the old asset (with certain adjustments). This allows the deferral of capital gains and maintains continuity in basis tracking, especially useful in real estate and business property exchanges.

Example – Substituted Basis

Alex exchanges a business truck (original basis: $20,000) for a similar truck in a like-kind exchange under IRC §1031.

He receives the new truck, valued at $25,000, but no gain is recognized due to the tax-free exchange rules.

Alex’s substituted basis in the new truck is the same as the old one: $20,000.

This maintains the original basis and postpones recognizing the gain until a taxable event takes place.

8. Tax Basis in Stock

For shareholders in corporations, especially in S corporations, the stock basis is crucial. It begins with the cost of acquiring the stock and is adjusted annually based on the corporation’s activity—such as income, losses, contributions, and distributions. The stock basis determines how much loss a shareholder can claim on their tax return and whether cash or property distributions are taxable.

Example

Morgan buys 100 shares of an S corporation for $10,000. Over the course of the year, she is assigned $3,000 in income and receives a distribution of $1,000.

Her tax basis in stock is:

$10,000 (initial investment)

- $3,000 (income)

– $1,000 (distribution)

= $12,000

This basis helps determine how much loss she can deduct and if future distributions are taxable.

9. Basis in Debt (for S Corporations)

In addition to stock basis, S corporation shareholders may also have a basis in loans they make directly to the corporation. This loan basis enables shareholders to claim losses exceeding their stock basis, limited to the amount of their debt basis. However, unlike partnership debt basis rules, shareholders must personally lend the money to obtain this additional basis—it cannot come from third-party bank loans guaranteed by the shareholder.

Example – Basis in Debt (S Corporation):

Tom is a shareholder in an S corporation. He loans $15,000 directly to the corporation when it needs working capital.

This loan provides Tom with a $15,000 debt basis, which is distinct from his stock basis.

If the company incurs a loss of $20,000, and Tom’s stock basis is only $10,000, he can deduct the first $10,000 from stock basis and the remaining $10,000 from his $15,000 loan basis.

After claiming the deduction, his remaining debt basis is reduced to $5,000.

10. Basis in Mutual Funds

Mutual fund investors must track their basis per share, which can change over time due to reinvested dividends and capital gains. The IRS allows different methods to calculate this basis, including average cost basis, FIFO (first-in-first-out), and specific identification. The choice of method affects the gain or loss recognized upon sale of mutual fund shares and must be applied consistently.

Example – Basis in Mutual Funds:

Priya buys mutual fund shares for $8,000 and later reinvests $2,000 in dividends.

Her basis in the mutual fund becomes $10,000 ($8,000 + $2,000 reinvested).

If she sells all the shares later for $13,000, her capital gain is $3,000.

Summary Table of Tax Basis Types

| Type of Basis | How It’s Determined | Used For |

| Cost Basis | Purchase price + related costs | All assets |

| Adjusted Basis | Cost + improvements – depreciation | Gain/loss on sale, depreciation |

| Carryover Basis | Donor’s basis (gifted assets) | Gifted property |

| Stepped-Up Basis | FMV on date of death | Inherited property |

| Substituted Basis | Old basis adjusted in a non-taxable exchange | 1031 exchange, involuntary conversion |

| Pass-Through Entity Basis | Contributions + income – losses – distributions | Partnerships & S corporations |

| AMT Basis | Adjusted basis under AMT rules | AMT gain/loss calculations |

| Installment Sale Basis | Basis allocated across payments | Installment sales under IRC §453 |

| Debt Basis (Partnerships only) | Share of partnership debt | Increases deductible loss limits |

Summary

Understanding the right type of basis is essential for correctly calculating gain, loss, depreciation, and deductions. The type of transaction or how an asset is acquired determines which basis rules apply. Whether you’re dealing with a gift, inheritance, pass-through entity, or real estate, the correct basis will ensure accurate reporting and strategic tax savings.

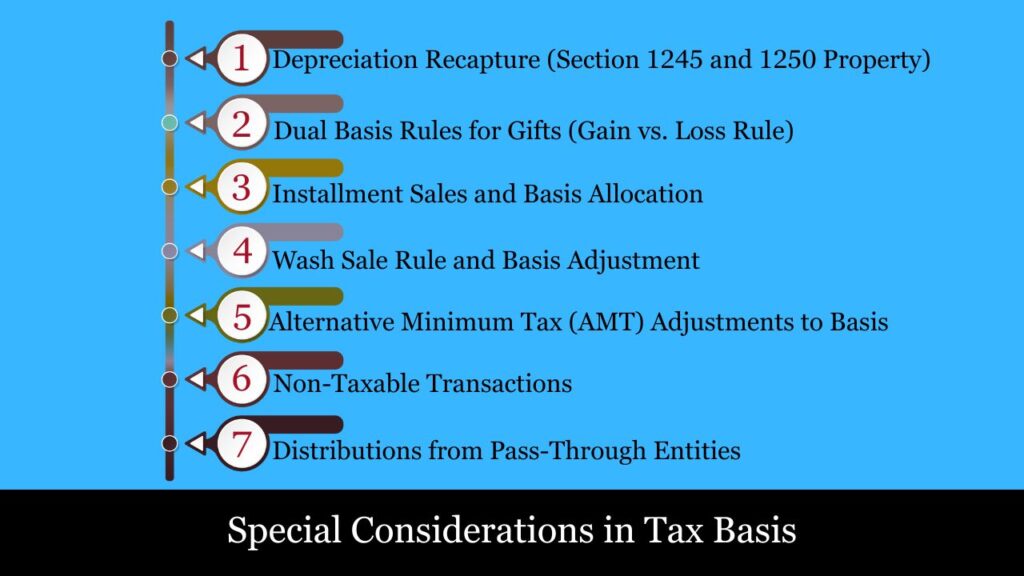

Special Considerations in Tax Basis – With Calculations and Examples

While tax basis is often straightforward (cost + improvements – depreciation), several special tax rules can cause significant deviations from the norm. These situations require adjustments, exceptions, or detailed calculations that affect how the IRS treats basis and ultimately, how much tax is due.

1. Depreciation Recapture (Section 1245 and 1250 Property)

When you depreciate property for tax purposes, the adjusted basis is reduced. But when that asset is sold, some or all of the prior depreciation may be recaptured and taxed as ordinary income, not capital gain.

Example: Section 1245 Recapture (Machinery)

- Purchase Price: $100,000

- Depreciation Taken: $60,000

- Adjusted Basis: $100,000 – $60,000 = $40,000

- Sale Price: $90,000

Calculation

- Gain Realized = $90,000 – $40,000 = $50,000

- Recaptured Ordinary Income = Lesser of:

- Depreciation taken = $60,000

- Gain = $50,000

So, $50,000 is taxed as ordinary income

2. Dual Basis Rules for Gifts (Gain vs. Loss Rule)

Gifted property comes with two different basis rules:

- For gains, you use the donor’s adjusted basis (carryover basis).

- For losses, you use the fair market value (FMV) on the date of gift if FMV is less than the donor’s basis.

- If the sale price falls between the two, there’s no gain or loss.

Example: Dual Basis Gifted Asset

- Donor’s Basis: $50,000

- FMV at Gift: $40,000

- You sell it for:

- $60,000 → Use donor’s basis → Gain = $60,000 – $50,000 = $10,000

- $30,000 → Use FMV → Loss = $30,000 – $40,000 = $10,000

- $45,000 → Falls between → No gain or loss

This rule prevents using the loss in value from before the gift to reduce taxable income.

3. Installment Sales and Basis Allocation

When property is sold under an installment sale, the gain is recognized over time, as payments are received. The tax basis must be allocated proportionally to principal payments.

Example: Installment Sale of Property

- Sale Price: $100,000

- Adjusted Basis: $40,000

- Gross Profit = $100,000 – $40,000 = $60,000

- Gross Profit % = $60,000 ÷ $100,000 = 60%

- Each year, you receive $10,000 in principal → $6,000 of that is taxable gain

This applies under IRC §453 and is especially useful for property sold over multiple tax years.

4. Wash Sale Rule and Basis Adjustment

A wash sale happens when an investor sells a security at a loss and repurchases a substantially identical one within 30 days before or after the sale date. The IRS disallows the loss, and the disallowed loss is added to the basis of the new security.

Example: Wash Sale Rule

- Sold: 100 shares of XYZ at $2,000 (original basis = $3,000) → $1,000 loss

- Reacquired same stock 5 days later for $2,200

- Wash sale applies → Loss disallowed

New basis = $2,200 + $1,000 = $3,200

When eventually sold, the $1,000 loss will reduce the gain or increase the loss.

5. Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) Adjustments to Basis

For AMT purposes, certain deductions like accelerated depreciation are added back, and this can lead to a different AMT basis than regular tax basis. This is especially relevant when disposing of property previously depreciated more rapidly under MACRS.

Example: AMT Adjustment on Sale of Property

- Depreciation (MACRS – regular tax): $40,000

- Depreciation (AMT): $30,000

- Tax Basis = $100,000 – $40,000 = $60,000

- AMT Basis = $100,000 – $30,000 = $70,000

Impact: If sold for $90,000:

- Regular tax gain = $90,000 – $60,000 = $30,000

- AMT gain = $90,000 – $70,000 = $20,000

This $10,000 difference is reported as an AMT adjustment on Form 6251.

6. Non-Taxable Transactions (Like-Kind Exchange – Section 1031)

For certain non-taxable transactions like 1031 exchanges, the basis of the new asset is not reset to FMV. Instead, you carry forward the old basis with some adjustments.

Example: Like-Kind Exchange

- Old Building:

- FMV = $300,000

- Adjusted Basis = $120,000

- You receive:

- New Building worth $280,000

- Cash (boot) = $20,000

- Recognized Gain = Lesser of:

- Boot received = $20,000

- The total gain realized is calculated as $300,000 minus $120,000, resulting in a gain of $180,000

Recognized gain = $20,000

New basis in replacement property =

= Old basis + Gain recognized – Boot received

= $120,000 + $20,000 – $20,000 = $120,000

7. Distributions from Pass-Through Entities

For partnerships and S corporations, basis affects whether a distribution is taxable. Distributions reduce basis first, and any excess is a taxable capital gain.

Example: Distribution from S Corporation

- Stock basis before distribution = $25,000

- Distribution = $30,000

Result

- First $25,000 = tax-free return of capital

- Remaining $5,000 = capital gain

After distribution, your stock basis becomes $0.

Summary Table of Special Basis Adjustments

| Scenario | Basis Adjustment | Tax Impact |

| Depreciation | Decreases basis | Recapture ordinary income |

| Capital improvements | Increases basis | Lowers taxable gain |

| Inherited property | Step-up to FMV | Eliminates past gains |

| Gifted property | Dual basis rule | Gain/loss depends on sale price |

| Wash sale | Adds disallowed loss to new stock | Delays loss recognition |

| AMT | Higher AMT basis | Lowers AMT gain |

| Installment sale | Allocated basis | Gain recognized over time |

| 1031 exchange | Substituted basis | Defers gain, doesn’t eliminate |

| Distributions > basis | Excess is capital gain | Reduces basis first |

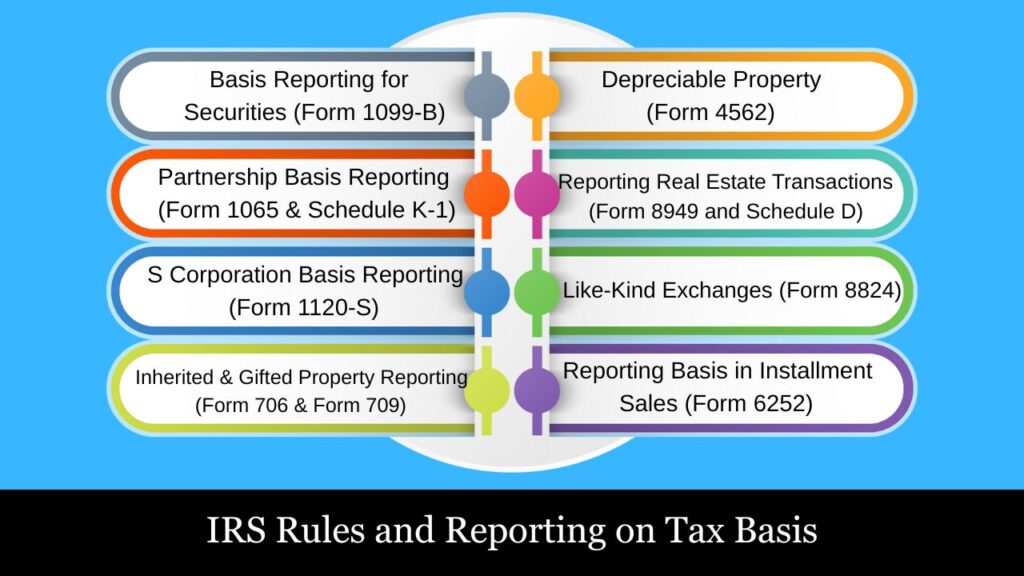

IRS Rules and Reporting on Tax Basis

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) requires taxpayers to maintain accurate records of tax basis to correctly report income, calculate deductions, and determine gain or loss on the sale or disposition of property. Tax basis reporting is not only a compliance requirement but also a key part of accurate tax liability determination.

1. Basis Reporting for Securities (Form 1099-B)

For stocks, bonds, and mutual funds, brokers must report the cost basis of covered securities on Form 1099-B, providing details such as the purchase date, sale proceeds, and classification of the gain or loss as short-term or long-term, to both the IRS and the taxpayer. Taxpayers must match their reported capital gains on Schedule D (Form 1040) with these details. If the taxpayer disagrees with the broker’s reported basis, they must provide documentation to support their figures.

2. Partnership Basis Reporting (Form 1065 & Schedule K-1)

In a partnership, tracking both the inside basis—the partnership’s basis in its assets—and the outside basis—the individual partner’s basis in their ownership interest—is crucial for accurate tax reporting. While the partnership tracks inside basis, individual partners must track their outside basis, which determines the deductibility of losses and tax treatment of distributions. The IRS requires partnerships to report each partner’s share of income, deductions, and distributions on Schedule K-1 (Form 1065). In addition, partnerships may need to disclose basis computations if required for loss limitation rules.

3. S Corporation Basis Reporting (Form 1120-S and Shareholder Worksheets)

Shareholders of S corporations must maintain both stock basis and loan basis. While the IRS does not require S corporations to report shareholders’ basis on a tax form, Rev. Proc. 2017-09 strongly encourages taxpayers to use a basis computation worksheet to determine allowable losses and tax-free distributions. In audit situations, lack of proper basis tracking can lead to disallowed losses.

4. Inherited and Gifted Property Reporting (Form 706 & Form 709)

For inherited property, the IRS uses a stepped-up basis approach and requires estate representatives to report asset values on Form 706 (Estate Tax Return). For gifted assets, the carryover basis is used, and the donor must file Form 709 (Gift Tax Return) if the gift exceeds annual exclusion limits. These filings help the IRS track correct basis for future capital gain calculations.

5. Depreciable Property (Form 4562)

When depreciable business assets are placed in service, their cost basis must be reported on Form 4562 to calculate allowable depreciation. The basis is adjusted annually for depreciation taken, which is required to be reported and tracked over the asset’s life. This adjusted basis is crucial when the asset is sold or retired.

6. Reporting Real Estate Transactions (Form 8949 and Schedule D)

For real estate, taxpayers must report the adjusted basis of property sold on Form 8949, which flows into Schedule D. Adjustments include improvements, depreciation, and selling expenses. If a portion of gain qualifies for exclusion under Section 121 (sale of primary residence), it must be properly indicated on the form.

7. Like-Kind Exchanges (Form 8824)

In like-kind exchanges under IRC §1031, the IRS requires detailed basis tracking on Form 8824, where the substituted basis of the replacement property is reported. This allows the IRS to verify that deferred gains are accurately calculated and carried forward.

8. Reporting Basis in Installment Sales (Form 6252)

When selling property on an installment basis, the IRS requires taxpayers to report the gross profit percentage and basis allocation on Form 6252. The basis is used to determine what portion of each payment is return of capital versus taxable gain.

Conclusion: Why Tax Basis Matters

Tax basis is not just a technicality—it directly affects how much tax you pay. Misreporting basis can result in:

- Overpayment of capital gains tax

- Disallowed loss deductions

- IRS penalties for inaccurate reporting

Whether you’re managing personal investments, selling real estate, or involved in a pass-through entity, having a firm grasp on tax basis is essential for strategic tax planning, accurate compliance, and avoiding costly errors.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How is cost basis determined?

It generally represents the amount you paid for the asset, along with any associated acquisition costs.

What is stepped-up basis?

It resets the basis of an inherited asset to its fair market value as of the decedent’s date of death.

What is carryover basis?

It means the person receiving the gift assumes the donor’s original basis in the asset.

Why is outside basis important in partnerships?

It determines your share of losses, distributions, and gain or loss on exit.

What is the role of debt basis in S corporations?

It allows shareholders to deduct losses beyond stock basis, up to the amount they personally loaned to the company.

Which IRS form reports stock basis in sales?

Form 1099-B provides details of stock sales, including cost basis information for covered securities, to assist in calculating capital gains or losses.

Can basis be negative?

No, If losses exceed basis, the excess is suspended until basis is restored.